Skeuomophia: a Digital Fashion Film

Designers Finn and Dylan scan archival fashion

Amsterdam Museum

Interview with Dylan Eno and Finn van Tol

On August 22nd, the Amsterdam Museum opened a mini-exposition: “Unboxing: Fashion from the Archives”.

The exhibition explored how archival fashion could be displayed in a new way, to broaden the way how we look at, interact with and think about fashion in museums.

Designers and filmmakers Finn van Tol and Dylan Eno create life-like digital doubles of archival fashion. Their short film “Skeuomorphia” is the result of a collaboration with the Amsterdam Museum for this exhibition.

After visiting the exhibition’s opening, Charlotte from Blauw Films initiated a conversation with Dylan and Finn to chat about the interplay between fashion heritage, 3D workflows and filmmaking.

Digitalising fashion heritage, filmmaking and collaborating with museums. We’ll talk about it all in a second, but first, would you mind introducing yourselves and what you do?

Finn: I’m Finn. Finn van Tol. I’m an interdisciplinary designer. I work a lot with history and heritage, in relation to fashion as to interior and design objects. I studied at the Design Academy Eindhoven, where I met Dylan.

Dylan: I’m Dylan Eno. I always say that I like to work around fashion, around clothes. I very much like to put clothing and fashion in an atmosphere, and create a story. I’ve been doing that together with Ronald Van Der Kemp, a couture designer from Amsterdam. Lately I’ve been getting involved with the world of archival fashion and finding ways to tell the stories of those pieces that can’t be physically displayed anymore.

I’m curious to hear your perspectives on what the film medium has to offer in the context of museums and exhibitions.

Dylan: For me, I can say I like film because it’s time-based. You have a specific amount of time, and you can choose when to give the audience what part of the information. Like a book, you can guide someone through the story. When they’re five minutes in, I want them to know this, when they’re ten minutes in, I want them to know this, etcetera. Compared to a book, film is extremely immersive. You can work with both sound and moving imagery, that combination makes it my preferred medium.

Finn: You can use film to shape the view of the audience. In a way, you can force them what to look at, which is a powerful way to convey information. Film allows you to visualise a lot of multi-layered information, while making sure the viewer congests the material in a way you want them to. I believe it’s a very time-efficient medium.

In the type of projects that you guys make, objects become the characters that tell the story. How does this type of storytelling through objects work?

Finn: It feels sometimes, like we’re making a visual essay. You could translate what we want to say into an essay. It’s what we do in preparation anyway, in conversation and with drawings. We put objects together and discuss how their relation visualises or expands the narrative. What is the narrative created between objects, and how does it help us to visualise the information and story?

It’s quite some research that we do on the subject of each object. We read a lot, and speak to historians. We try to understand the time that the object is from, and how it influenced all the other objects that came after it.

Our short film shows this as well. Objects evolve. It’s really through skeuomorphia, that design DNA gets mixed into the next generation. We try to find where history and design language meet, and use that to visualise a story.

Dylan: Whenever we work with historians, it’s the object that connects us to each other. Everyone looks at an object through their own specialised lens, and these perspectives we share and discuss. This research is the basis of how we produce our work.

What is exactly the concept behind your short film “Skeuomophia”?

Finn: "Skeuomophia" is derived from the term skeuomorphism. This is a design principle in which an object derives its shape and material language from another object, to convey its use. A metal harness is a base design that quite some objects have evolved from. Skeuomorphism is the red thread that runs through our film. We relate the male torso to the metal harness, the harness to a jerkin, and eventually the jerkin to a waistcoat and shirt.

In terms of a historical timeline, these objects are far apart. But what we found is that the metal harness seems to be the starting point for male fashion. When you look at how the torso is divided, and how it is designed to accentuate the male form. That’s skeuomorphism. The harness exaggerates the shape of the perfect male body to convey notions of masculinity such as strength and protection but also wealth and status. A jerkin conveys the same design language, but in a more wearable material.

Dylan: I think it’s also worth mentioning that the harness we used wasn’t used in battle. It’s not part of an armor. It was purely worn to display wealth, status and taste.

What would you say is the value of using 3D scanning techniques in relation to fashion heritage, in comparison to filming the object.

Dylan: I think that to us using photogrammetry is an obvious choice, because it’s a technique that inspires us. I always like to say, John Galliano uses the bias cut, and I use photogrammetry. The tool and technique fuels our inspiration.

What I find so fascinating about it, is that you have this object that exists somewhere in a depot and by creating a digital twin you can display the object however you want. You can put it in a different environment for example. This way you can always adjust the context and the story you want to tell about the object. I actually think it’s very important to have a digital reproduction that comes as close as possible to the real thing.

In “Skeuomorphia” we use the digital harness to talk about the shape. But in the future, someone could use the same file to talk about the decorations. There is no singular historical point of view, there are many many angles from which an object could be viewed. Digital copies give the perfect opportunity to rethink the object’s context.

Finn: It’s also just nice that while you’re working on your project, you are actually archiving history. I think it gives an extra layer to your process and the work. You are not just creating your own story, but also increasing the possibility of more stories being told. National heritage is for everyone, and the digital twin increases the accessibility to an object.

Dylan: What I also find fascinating about using 3D models for storytelling, is the value the two add to each other. An object needs to be 3D scanned because it has an interesting story, and once you have it as a 3D model, you can use it to talk about the story way easier. So the 3D scan needs stories, but the story is also needed to justify the relevance of the 3D scan. There is this real interplay between the two dependencies.

Finn: For production reasons, photogrammetry is nice because you only have to shoot on location once. Especially when dealing with heritage and scheduling shooting days, this is great. We can always use the 3D model to revisit the object. We can study the details whenever we want, and create as many shots as we want.

And funnily enough, the mesh of an object can tell you a lot about the object itself as well. It can for example reveal imperfections that aren’t visible to the naked eye.

Dylan: The photos we took of the harness are without reflection, and revealed for example so much more rust. It even revealed an imperfection caused by a piece of tape someone once put on it. It doesn’t show in real life, but it was very apparent on the diffuse map. For conservatory and restoration practices this is actually very valuable information.

The potential of digital archives for the preservation of cultural heritage is a very interesting subject. What are your thoughts on this?

Dylan: There seem to be three big factors in the world of cultural heritage where digitalising could add value.

Firstly there is the natural degradation of the objects. For example, we’re now seeing that objects from the 80’s start to fall apart at a rapid pace, because of all the plastic materials they started to use. Nobody understood how these materials hold up in the long run. If we don’t 3D scan these objects now, maybe we won’t have any fashion left from the 80’s in a hundred years. Perhaps it’s all gone.

Then there is of course the effect of unexpected events. I know of a museum that got flooded, and all objects in the depot were damaged by the water. Or even worse, war can deal tremendous damage to cultural heritage. If we don’t start to develop alternatives to archive objects, they can be gone within moments. It’s all so fragile at the end of the day.

Lastly, as soon as the object is transferred to the digital sphere, it opens up a whole new way of looking at the object. We can view it through different lens lengths, under a variety of lighting conditions, zoom in and out, turn it around, etcetera.

It is inspiring for the curators and conservators also, because the digital double unlocks new tools for them as well.

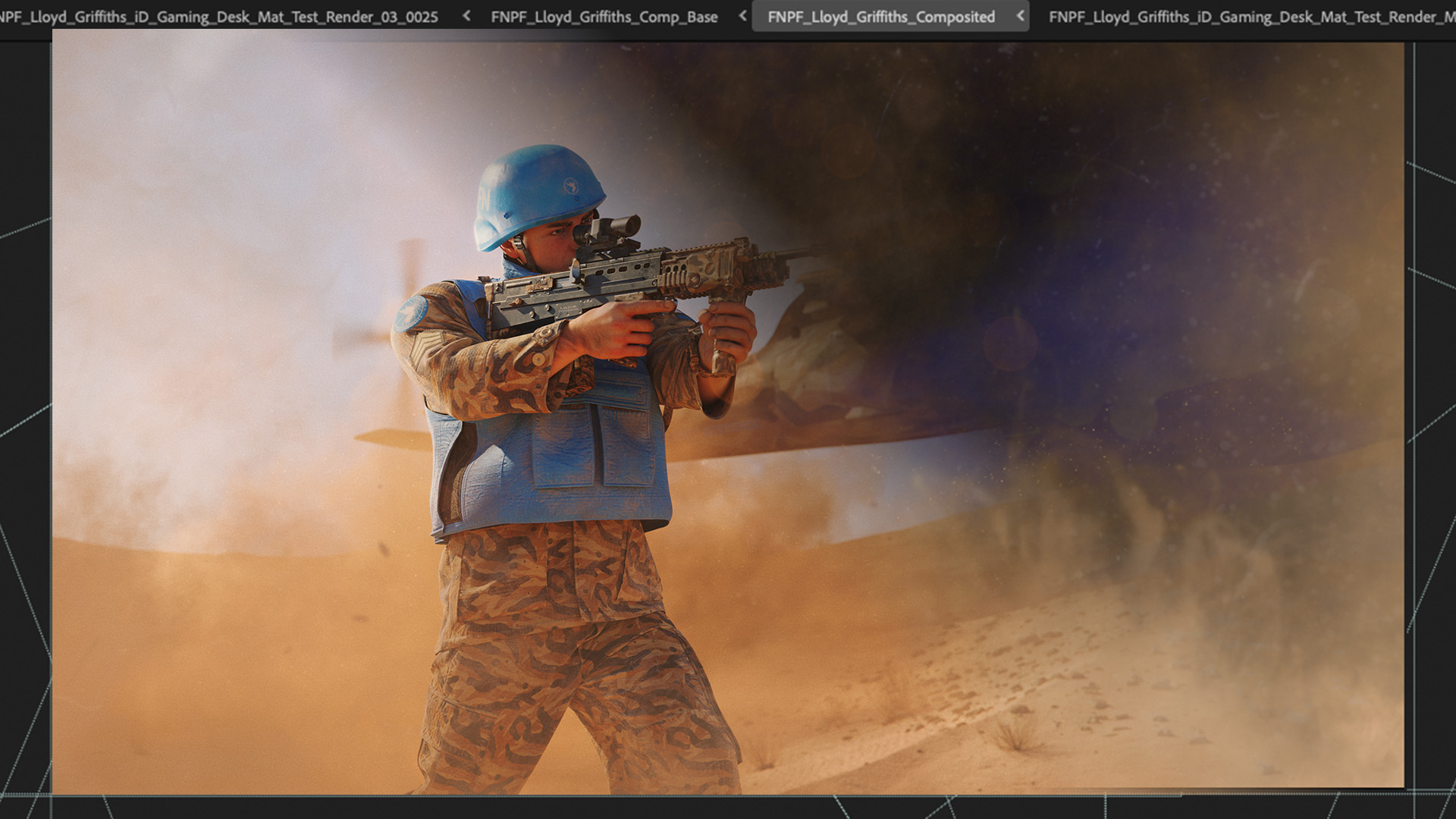

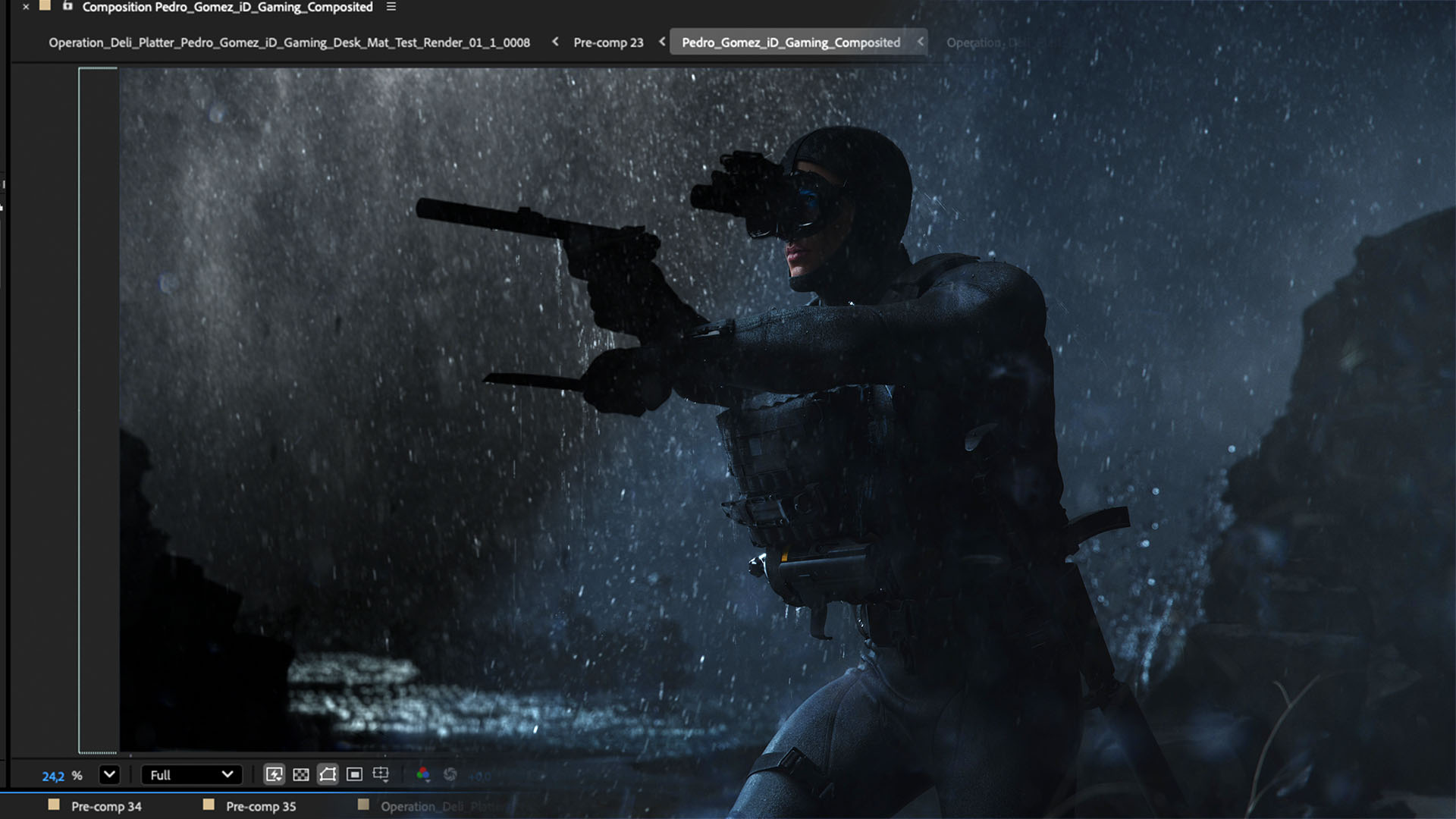

Finn: Right now, a lot of cultural heritage is being scanned by the gaming industry. Somehow the gaming industry stumbled their way into being one of the most important players in the of cultural heritage archiving. But we have to think about what this means, because in reality the gaming companies keep these files mostly for themselves. It’s not necessarily shared with the museums or the public.

When the Notre Dam burned in Paris, the municipality approached Ubisoft, because a couple of years before they had scanned the Notre Dam for Assassin's Creed. Games like Call of Duty scan an immense amount of uniforms and gear, but it’s hard for individual creators to approach them and ask for the files, even if it’s for non-commercial purposes.

If museums would open up budgets to create these scans and build a digital archive, the bridges between game and cultural heritage could perhaps be built in a more accessible and mutually beneficial manner. Perhaps not on purpose, but it’s almost like digital archives are being gatekept by game companies. Which is really strange.

When looking for objects to include in your film, how did you set up contact with the Amsterdam Museum and convince them to scan objects?

Dylan: As part of a bigger project we really wanted to 3D scan a harness. Both because we needed the object for the story of skeuomorphism, but also because we wanted to experiment and learn about how to scan such a reflective surface.

We knew that certain museums are very hard to contact, and those that are much easier to approach. That usually depends on how open-minded the head of conservation is. We knew that Roberto at the Amsterdam Museum is super open-minded to these things. So we contacted him, and from there on onwards it was easy sailing, because he understands the importance of these projects.

How did you guys approach the trial and error process of scanning such a complex object? It’s notoriously hard to 3D scan metals.

Dylan: What’s worth mentioning is that we use photogrammetry. 3D scanning harnesses with a hand scanner has been done before, but it’s a completely different technique. We want to use photogrammetry because it results in very high quality textures.

It took some experimentation to achieve the results we wanted. We started at home with metals that weren’t as reflective, and we sort of worked our way up and increased the complexity of the objects along the way. We were very lucky to get a test-day at the Amsterdam Museum depot. That’s very rare, actually. The final scan took us an entire day. They were very generous with the amount of time they were able to offer us.

Finn: A lot of industries use a chalk-spray to take away the gloss of an object. Of course, we absolutely cannot do this with archival objects. Although the chalk spray doesn’t damage the object, the museums wouldn’t like the idea of spraying some stuff on their pieces. But then again, the authentic texture is so important to us, we wouldn’t want to alter it anyway.

Dylan: Because we were able to do so many tryouts, we tried out a variety of stitching software to create the final 3D model. In the end, we used a different software for the chestplate and the shoulder pieces. There is so much information available online on 3D scanning. Although it’s unlikely you’ll find a complete breakdown on how to process your specific item, by piecing together parts of various videos and tutorials, we worked out how to tackle the harness. It’s not like we were inventing the wheel, but we had to frankenstein a workflow in order to create our wheel, so to say.

I’m curious to hear more about this future ‘bigger project’ you mentioned. What is it that you’re working on?

Finn: We’re still developing the specifics of it, but the big project we’re working on right now focuses on how military clothing is influenced by popular culture. You often hear how pop fashion is influenced by military design, but the same is true the other way around. The military really looks at trends, in order to attract and inspire young people or influence public perception. It’s all about street-cred and the feeling that a uniform gives the wearer. The military understands the importance of this.

The items we are gathering right now are all military items. We’re looking at historical items from the mediaeval ages, but also clothes that might not yet be considered cultural heritage, such as modern uniforms and fashion which has design elements that have found its way into military uniforms. Workwear also uses a similar design language as the military, so we’re researching these influences as well.

Dylan: The next object we’ll be scanning is a gambeson, which is sort of the predecessor of the jerkin. Then there is my personal holy grail object, which is a jerkin from the Rijksmuseum, which we’re still trying really hard to be allowed to scan. We’re also interested in diving a little bit deeper into the 18th century. In the end we want to include modern fashion to relate it all back to our current reality.

Finn: I’ve found it to be really nice to start archiving outside of the traditional heritage world. As a lot of curators recognize that everyday modern objects hold value as well, they can represent the part of history that we are currently living.

Thank you to Finn and Dylan for this chat and sharing their insights with us!

A special thanks to Roberto Luis Martins, Curator fashion and Popular Culture at the Amsterdam Museum, for inviting us to the opening of Unboxing: Fashion from the Archives.

Reading List

References

- Amsterdam Museum — Amsterdam Museum Homepage

- Unboxing: Fashion from the Archives — Amsterdam Museum

- Dylan Eno — Dylan Eno

- Fin van Tol — Instagram

- Design Academy Eindhoven — Wikipedia

- Ronald van der Kemp — Wikipedia

- Skeuomorph— Wikipedia

- Jerkin — Wikipedia

- Photogrammetry — Wikipedia

- John Galliano — Wikipedia

- Gambeson — Wikipedia

.jpg)

%20by%20Ivan%20Aivazovsky.jpg)

0 Comments